An article will help you understand what the principle of inductors is

Understanding the Principle of Inductors

I. Introduction

Inductors are fundamental components in electrical circuits, playing a crucial role in the behavior and functionality of various electronic devices. Defined as passive electrical components that store energy in a magnetic field when electrical current flows through them, inductors are essential for managing current and voltage in circuits. This article aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of inductors, exploring their basic concepts, underlying physics, construction, behavior in circuits, applications, and practical considerations.

II. Basic Concepts of Inductance

A. Definition of Inductance

Inductance is the property of an electrical conductor that allows it to store energy in a magnetic field when an electric current passes through it. The ability of an inductor to store energy is quantified by its inductance, which is measured in henries (H). One henry is defined as the inductance of a circuit in which a change in current of one ampere per second induces an electromotive force (EMF) of one volt.

B. Historical Background

The concept of inductance is rooted in the discovery of electromagnetic induction, which was first observed by Michael Faraday in the 1830s. Faraday's experiments demonstrated that a changing magnetic field could induce an electric current in a nearby conductor. This principle laid the groundwork for the development of inductance theory, further advanced by key figures such as Joseph Henry, who independently discovered self-induction and mutual induction.

C. Units of Inductance

Inductance is measured in henries (H), named after Joseph Henry. The relationship between inductance and other electrical units is significant; for instance, one henry is equivalent to one volt per ampere per second. Understanding these units is essential for engineers and technicians working with inductors in various applications.

III. The Physics Behind Inductors

A. Electromagnetic Principles

The operation of inductors is governed by two fundamental laws of electromagnetism: Faraday's Law of Electromagnetic Induction and Lenz's Law.

1. **Faraday's Law of Electromagnetic Induction** states that a change in magnetic flux through a circuit induces an electromotive force (EMF) in that circuit. This principle is the foundation of how inductors function, as the current flowing through the inductor creates a magnetic field that can change over time.

2. **Lenz's Law** complements Faraday's Law by stating that the direction of the induced EMF will always oppose the change in current that created it. This opposition is what gives inductors their unique behavior in circuits, particularly in response to changes in current.

B. How Inductors Store Energy

Inductors store energy in the form of a magnetic field. When current flows through an inductor, it generates a magnetic field around it. The energy (W) stored in this magnetic field can be expressed mathematically as:

\[ W = \frac{1}{2} L I^2 \]

where \( L \) is the inductance in henries and \( I \) is the current in amperes. This equation illustrates that the energy stored in an inductor increases with the square of the current, highlighting the importance of current flow in energy storage.

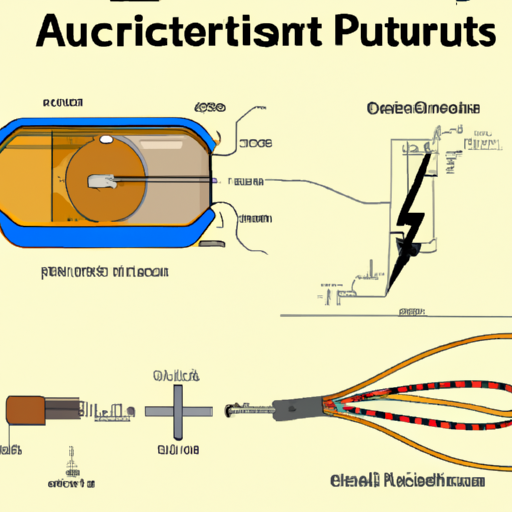

IV. Construction of Inductors

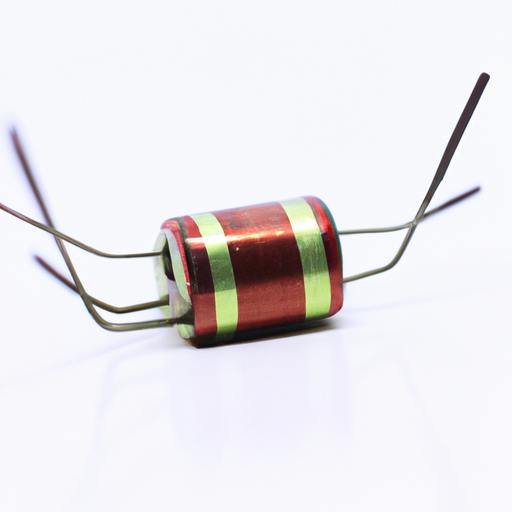

A. Basic Components of an Inductor

Inductors are typically composed of two main components: a core material and a winding of conductive wire.

1. **Core Materials**: The core can be made from various materials, including air, ferrite, or iron. The choice of core material affects the inductor's inductance and efficiency. Air-core inductors are often used in high-frequency applications, while iron and ferrite cores are used for lower frequencies due to their higher permeability.

2. **Wire Types and Winding Techniques**: The wire used in inductors can vary in gauge and material, with copper being the most common due to its excellent conductivity. The winding technique, whether solenoid, toroidal, or layered, also influences the inductor's performance.

B. Types of Inductors

Inductors come in various types, each suited for specific applications:

1. **Air-Core Inductors**: These inductors use air as the core material and are typically used in high-frequency applications due to their low losses.

2. **Iron-Core Inductors**: These inductors use iron as the core material, providing higher inductance values and better energy storage for lower frequency applications.

3. **Ferrite-Core Inductors**: Ferrite cores are used for their high magnetic permeability and low losses at high frequencies, making them ideal for RF applications.

4. **Toroidal Inductors**: These inductors have a doughnut-shaped core, which minimizes electromagnetic interference and provides efficient energy storage.

V. Inductor Behavior in Circuits

A. Inductive Reactance

Inductive reactance (XL) is the opposition that an inductor presents to alternating current (AC). It is defined by the formula:

\[ X_L = 2 \pi f L \]

where \( f \) is the frequency of the AC signal. This relationship shows that inductive reactance increases with frequency, making inductors more effective at blocking high-frequency signals while allowing low-frequency signals to pass.

B. Time Response of Inductors

Inductors exhibit unique time response characteristics in circuits, particularly in RL (resistor-inductor) circuits.

1. **Transient Response in RL Circuits**: When a voltage is suddenly applied to an RL circuit, the current does not immediately reach its maximum value due to the inductor's opposition to changes in current. The current increases gradually, following an exponential curve.

2. **Steady-State Behavior**: Once the circuit reaches a steady state, the inductor behaves like a short circuit, allowing current to flow freely.

C. Comparison with Capacitors

Inductors and capacitors are both energy storage devices, but they operate differently.

1. **Phase Relationships**: In an AC circuit, the current through an inductor lags the voltage by 90 degrees, while the current through a capacitor leads the voltage by 90 degrees. This phase difference is crucial in understanding how these components interact in circuits.

2. **Energy Storage Mechanisms**: Inductors store energy in magnetic fields, while capacitors store energy in electric fields. This fundamental difference leads to distinct behaviors in circuit applications.

VI. Applications of Inductors

A. Power Supply Circuits

Inductors are widely used in power supply circuits for filtering and smoothing voltage. They help reduce voltage ripple in DC power supplies and are essential components in switch-mode power supplies, where they store energy during one phase of operation and release it during another.

B. Radio Frequency Applications

Inductors play a vital role in radio frequency (RF) applications, such as tuned circuits and antennas. They help select specific frequencies and improve signal quality in communication systems.

C. Signal Processing

In audio equipment and communication systems, inductors are used for filtering and signal processing. They help eliminate unwanted noise and enhance the quality of audio signals.

VII. Practical Considerations

A. Selecting the Right Inductor for a Project

When choosing an inductor for a specific application, several factors must be considered:

1. **Inductance Value**: The required inductance value depends on the circuit's design and functionality.

2. **Current Rating**: The inductor must be able to handle the maximum current without saturating or overheating.

3. **DC Resistance**: Lower DC resistance is preferred to minimize power losses.

B. Inductor Limitations

Inductors have limitations that must be considered in design:

1. **Saturation**: When the magnetic core of an inductor reaches its saturation point, it can no longer store additional energy, leading to reduced inductance.

2. **Parasitic Capacitance**: Inductors can exhibit parasitic capacitance, which can affect their performance at high frequencies.

C. Safety Considerations

When working with inductors, safety is paramount. Proper insulation, heat dissipation, and current ratings must be adhered to in order to prevent overheating and potential hazards.

VIII. Conclusion

Inductors are essential components in electrical circuits, providing critical functions in energy storage, filtering, and signal processing. Understanding the principles of inductors, their construction, behavior, and applications is vital for anyone working in electronics. As technology advances, the development of new inductor materials and designs will continue to enhance their performance and expand their applications. We encourage readers to explore further and deepen their understanding of this fascinating topic.

IX. References

A. Suggested readings on inductors and inductance theory.

B. Online resources for further learning, including educational websites and video tutorials.

C. Academic papers and journals that delve into the latest research and advancements in inductor technology.

By understanding the principles of inductors, you can better appreciate their role in modern electronics and their impact on the devices we use every day.