-

- Contact Us

- Privacy Policy

- term and condition

- Cookies policy

F3L400R10N3S7FC1BPSA1 Datasheet: Critical Specs & Test Notes

F3L400R10N3S7FC1BPSA1 Datasheet: Critical Specs & Test Notes

Designers evaluating medium-voltage power stages care about a few headline numbers: a 950 V blocking rating, roughly 105 A continuous current class, and elevated maximum junction temperatures that target dense power conversion in three-level inverter, motor drive, and traction systems. This article walks through the F3L400R10N3S7FC1BPSA1 datasheet to extract the critical specs, show what to measure, and list test best practices so you can validate module performance quickly. The terms F3L400R10N3S7FC1BPSA1 and datasheet appear here to anchor the review.

1 — Quick overview & how to read the F3L400R10N3S7FC1BPSA1 datasheet

Part-number breakdown and module family role

Point: Decode the part-number fields to map the module to voltage, current and topology expectations. Evidence: The datasheet’s nomenclature groups family, current rating, and topology markers together. Explanation: Read the string left-to-right: family prefix → current/voltage class → topology hint (e.g., signals for three-level designs) → revision/package codes. Plain-language definition: this module is a chassis-mount power IGBT module intended as the power stage for medium-voltage converters and three-level inverter applications.

Package, pinout and mechanical constraints

Point: Mechanical details determine mounting, creepage, and thermal path; extract them first. Evidence: The datasheet lists package type, mounting method, creepage/clearance and terminal torque. Explanation: Pull package type (chassis/module), recommended terminal torque, isolation spec, and mounting footprint; confirm terminal labeling for gate/emitters and collectors. Below is a compact mechanical summary you should check against the datasheet:

| Item | What to extract |

|---|---|

| Package type | Chassis/module, mounting method |

| Pinout | Gate, emitter, collector locations and labels |

| Isolation/creep | Creepage, clearance, isolation voltage |

| Mechanical dims | Footprint, height, mounting hole pattern |

| Torque | Recommended terminal torque and washer specs |

2 — Critical electrical & thermal specs to extract (datasheet specs deep-dive)

Static/DC electrical parameters to highlight

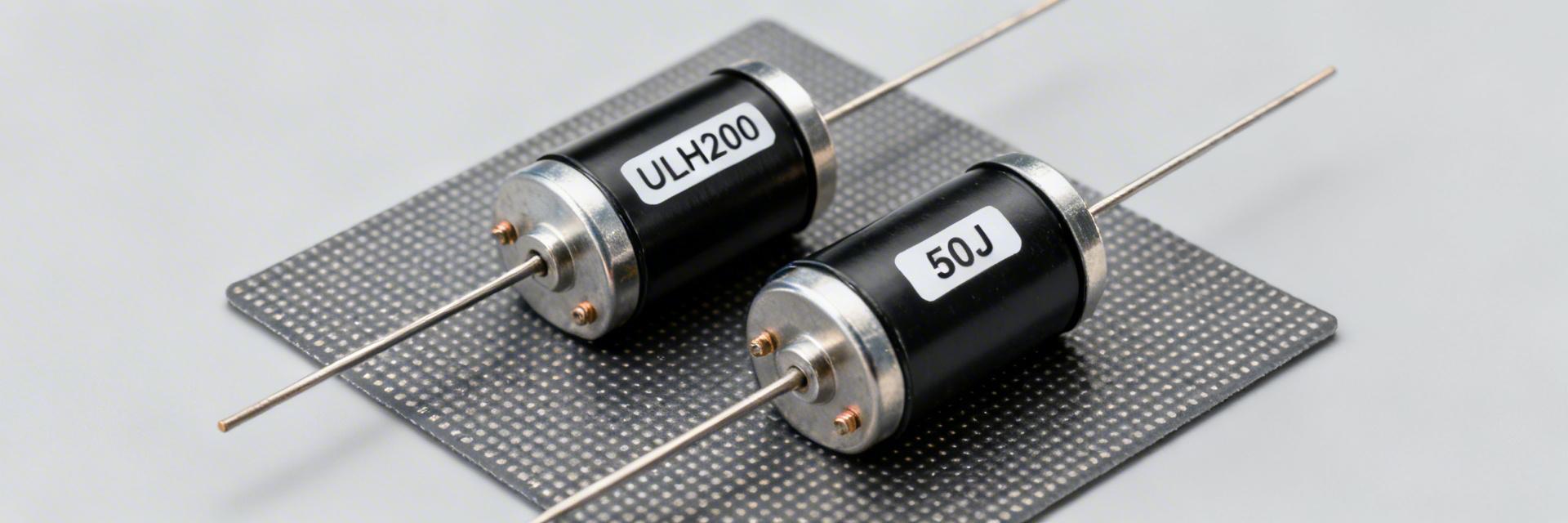

Point: Extract DC blocking voltage, continuous current and conduction losses with conditions. Evidence: The datasheet specifies VCE(0) (blocking voltage), continuous current class (~105 A), and VCE(sat) at defined Tj and Ic. Explanation: Record both typical and maximum VCE(sat) values with the test conditions (Tj, pulse width, VGE). Also note recommended gate-emitter voltage range and maximum VGE. Always capture whether the listed continuous current assumes a specified heatsink and ambient or a defined Tj.

Dynamic, thermal and reliability parameters to highlight

Point: Switching and thermal numbers drive loss budgeting and reliability. Evidence: Key entries include Eon/Eoff, turn-on/off times, Qg, Cies/Coss/Crss, Rth(j‑c)/Rth(j‑hs), Tj(max), and short‑circuit/SOA notes. Explanation: Pull energy per switching (Eon/Eoff) vs. current/di/dt curves, capacitances vs. VCE, and thermal resistances. Note derating limits (how Rth or allowable current changes with Tj) and any short‑circuit withstand pulse widths or required current limits for protection.

3 — Test notes: measurement setups and best practices

Recommended test setups & instrumentation

Point: Use controlled benches and low‑parasitic layouts to measure true device behavior. Evidence: Accurate switching-loss and VCE(sat) data depend on driver topology, series gate resistance, snubber design, and probe technique. Explanation: Checklist — isolated gate driver with Kelvin gate/emitter leads; two gate‑resistor sets (small for loss measurement, larger for application-level tests); low‑inductance bus‑bars; calibrated Rogowski or low‑resistor current sensing; differential/high‑bandwidth probes with minimized ground loops; and temperature control (heatsink + thermocouple at module case). Capture measurement point locations in a simple schematic before testing.

Common pitfalls and correction techniques

Point: Parasitics and probe setup commonly skew results. Evidence: Ringing from stray inductance or poor probe grounding inflates apparent Eon/Eoff and distorts VCE(sat). Explanation: Fixes include Kelvin sensing for VCE, use of short ground spring probe tips or high‑bandwidth differential probes, low‑inductance bus bars, and repeating tests with short pulse widths to avoid thermal buildup. Example: parasitic L combined with di/dt can create transient VCE spikes that falsely increase measured switching energy; add RC snubbers or clamp diodes and re‑measure to isolate device contributions.

4 — Interpreting performance data & thermal management strategies

From datasheet curves to real-world loss and Tj predictions

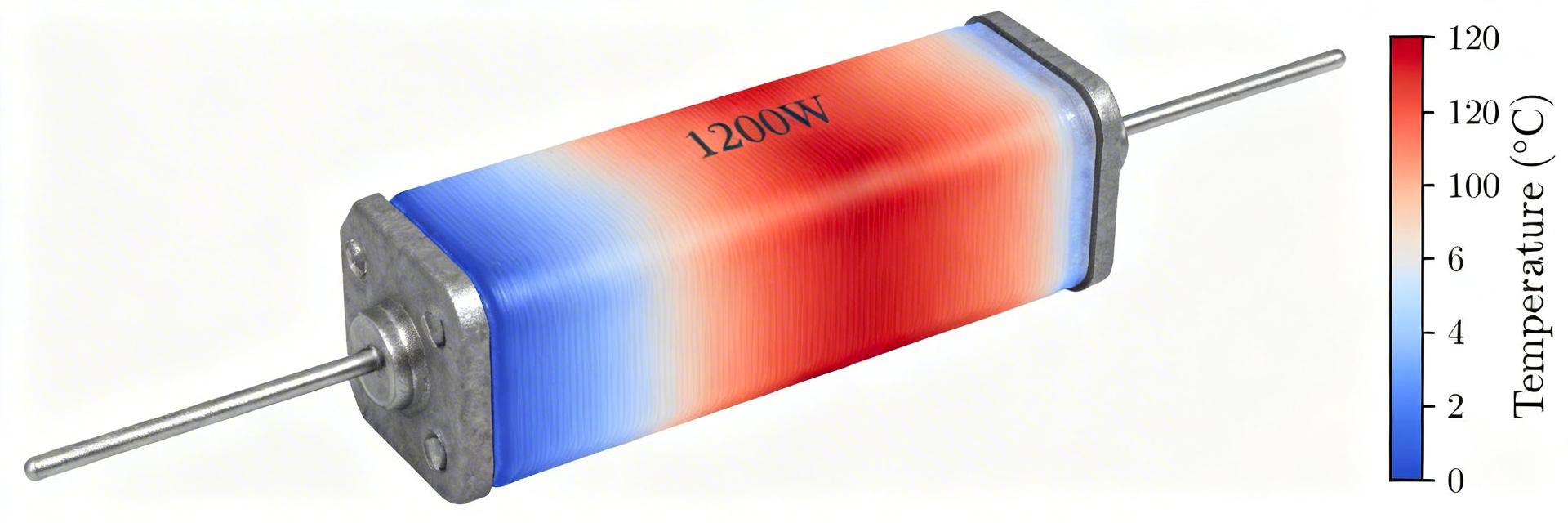

Point: Convert per‑pulse energies and conduction data into a system loss budget. Evidence: Datasheet gives Eon/Eoff and VCE(sat) curves; combine these with your operating point. Explanation: Use formulas: Pswitch = (Eon+Eoff)*fsw, Pcond = Ic(rms)*VCE_avg. Example workflow: pick fsw and duty, read Eon/Eoff at operating Ic/di/dt from curves, compute switching loss, add conduction losses, and apply Rth(j‑hs)+Rth(hs‑ambient) to predict Tj rise (ΔT = Psystem * Rth_total). Plot loss vs. ambient to inform heatsink selection.

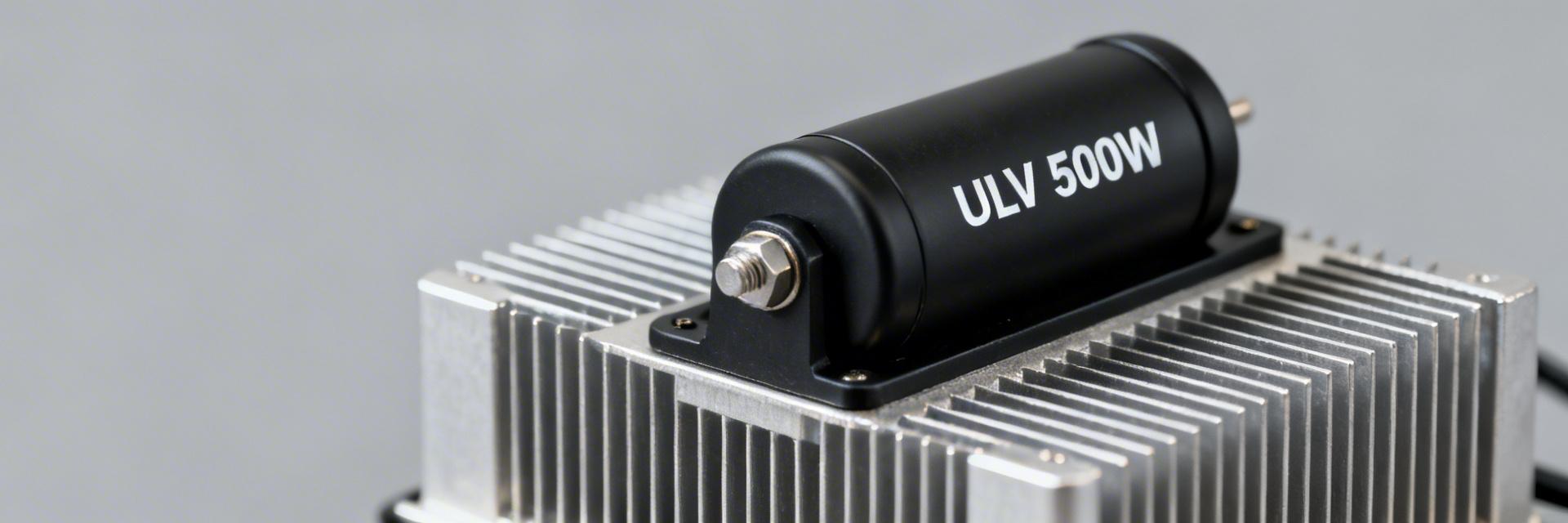

Cooling, mounting and lifetime considerations

Point: Proper TIM, mounting flatness and torque control extend life and reduce Rth. Evidence: Datasheet provides Rth and recommended mounting torque/flatness tolerances. Explanation: Use low‑outgassing, phase‑stable TIM and follow torque specs and flatness guidelines; verify contact resistance. For lifetime, apply thermal cycling and power‑cycling tests and apply Arrhenius or Coffin‑Manson style derating: higher Tj accelerates wear, so size thermal margin to keep Tj well below max during worst‑case ambient and fault conditions.

5 — Selection checklist & field troubleshooting guide (actionable takeaways)

Pre-purchase and design checklist

Point: A compact checklist avoids rework at procurement and PCB level. Evidence: Key criteria map back to datasheet entries for voltage/current margin, SOA, and thermal data. Explanation: Verify required voltage/current margins (≥ blocking voltage and ≥ continuous current with margin), switching-loss budget vs. fsw, SOA/short‑circuit pulse capability, package/mechanical fit, gate‑drive voltage and peak current compatibility, and thermal margin with heatsink sizing. Suggested procurement search phrases: "F3L400R10N3S7FC1BPSA1 switching loss measurement", "F3L400R10N3S7FC1BPSA1 thermal management".

On-board troubleshooting steps & symptom-to-test mapping

Point: Map symptoms to quick checks to reduce downtime. Evidence: Overheating or VCE(sat) rise often tracks to gate drive, contact or thermal issues. Explanation: Symptom → quick checks → targeted measurements: overheating → check heatsink contact, torque, TIM, capture case thermocouple; excessive VCE(sat) → verify gate drive amplitude, measure VGE and gate waveform, Kelvin sense VCE under pulsed conditions; switching transients → inspect layout parasitics, capture high‑bandwidth VCE and gate traces, and rework bus bars or snubbers as needed.

Summary

Pulling the F3L400R10N3S7FC1BPSA1 datasheet data you need means extracting blocking voltage (950 V), continuous current class (~105 A), VCE(sat) behavior and switching‑energy curves, plus thermal limits and SOA notes, then applying controlled measurement techniques and thermal calculations to predict real‑world performance. Following the outlined measurement setups, correction techniques and checklists reduces error, accelerates qualification, and makes system integration predictable; refer back to the F3L400R10N3S7FC1BPSA1 datasheet for the verified numeric conditions used in each test.

- Technical Features of PMIC DC-DC Switching Regulator TPS54202DDCR

- STM32F030K6T6: A High-Performance Core Component for Embedded Systems

- APT50GH120B Datasheet Deep Dive: Specs, Ratings & Curves

- SI3402-B-GMR PoE PD Controller: Market & Specs Report

- SI3402-B-GMR Benchmarks: Real PoE Performance Insights

- EFM8BB21F16G Full Datasheet & Pinout: Specs Summary

- CP2102N-A02-GQFN20R Pinout & Footprint: Quick Data Guide

- SI53307-B-GMR Datasheet & CAD Models: Quick Specs Checklist

- SI53361-B-GMR: Latest Specs, Stock Levels & Price Guide

- SI53340-B-GM: Deep Performance Report & Key Metrics

-

EXB-V4V120JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 12 OHM 0606

EXB-V4V120JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 12 OHM 0606 -

EXB-V4V473JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 47K OHM 0606

EXB-V4V473JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 47K OHM 0606 -

EXB-V4V823JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 82K OHM 0606

EXB-V4V823JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 82K OHM 0606 -

EXB-V4V151JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 150 OHM 0606

EXB-V4V151JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 150 OHM 0606 -

EXB-V4V181JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 180 OHM 0606

EXB-V4V181JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 180 OHM 0606 -

EXB-V4V331JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 330 OHM 0606

EXB-V4V331JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 330 OHM 0606 -

EXB-V4V152JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 1.5K OHM 0606

EXB-V4V152JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 1.5K OHM 0606 -

EXB-V4V563JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 56K OHM 0606

EXB-V4V563JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 56K OHM 0606 -

EXB-V4V104JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 100K OHM 0606

EXB-V4V104JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 100K OHM 0606 -

EXB-V4V154JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 150K OHM 0606

EXB-V4V154JVPanasonic Electronic ComponentsRES ARRAY 2 RES 150K OHM 0606