Online distributor prices for the SI5351A-B-GTR clock generator currently span roughly $0.59–$1.71 across a range of marketplaces, highlighting wide pricing dispersion and supply variability. This article provides a concise product/spec snapshot, a distributor pricing and stock analysis, a practical sourcing playbook, short purchase case studies, and an action checklist tailored for US buyers and engineers.

Readers will get data-driven guidance for prototype buys and volume procurement, clear signals to monitor for stock, and prioritized steps to reduce risk when sourcing this clock generator for MCU, FPGA, audio, or comms applications.

#1 — Product snapshot & key specs (Background)

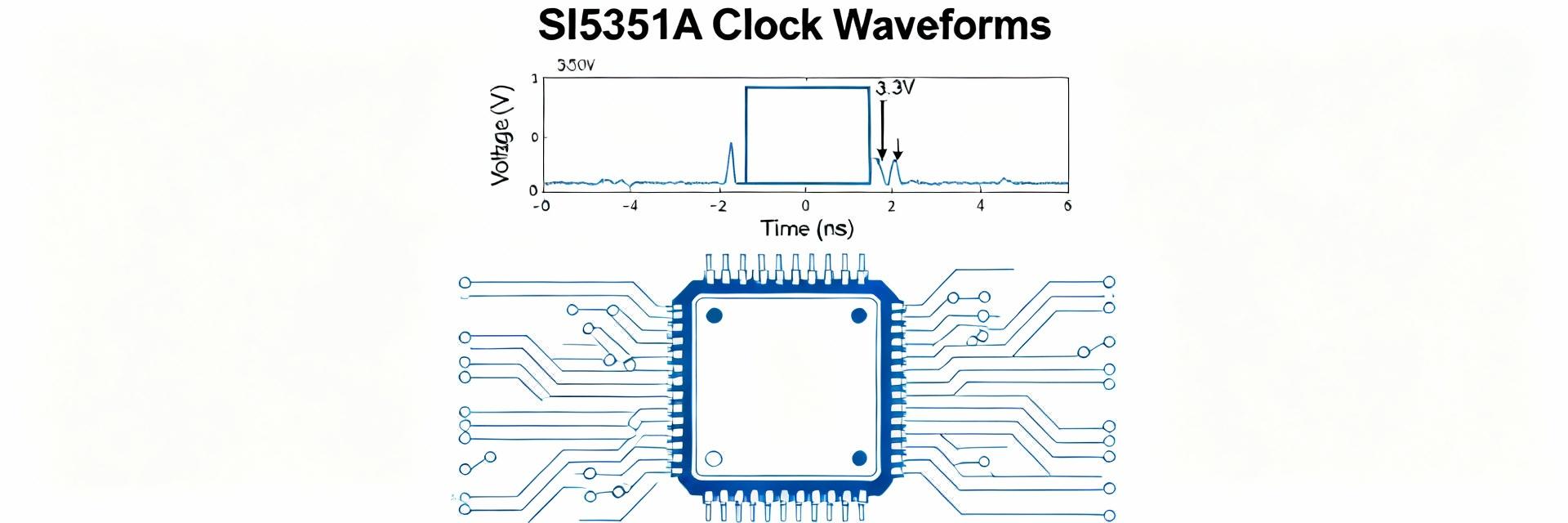

Core specs & packagelist essential electrical specs (output count, max freq 200 MHz, Vcc range, package MSOP10/10-TFSOP), key performance metrics to call out (jitter, power, I/O levels).

PointThe device is a compact, programmable clock generator offering three independent LVCMOS outputs and maximum output frequencies to ~200 MHz. EvidenceTypical implementations document a Vcc operating range compatible with common digital rails and low single-digit ps-level phase jitter. ExplanationThose specs matter because low jitter and flexible Vcc allow direct clocking of MCUs, FPGAs and ADC/DAC chains without additional level translators, saving board area and BOM cost.

Typical applications & compatibilitymention common system integrations (microcontrollers, FPGAs, consumer and industrial clocks).

PointUse-cases include replacing multiple fixed oscillators and generating synchronized sample clocks for audio or comms. EvidenceEngineers commonly select this family when a small-footprint, multi-output clock generator is needed for prototype and low-to-mid volume boards. ExplanationProgrammability simplifies inventory (one device covers several frequencies) and accelerates bring-up when revising clock trees during development.

#2 — Pricing landscapedistributor comparison & trends (Data analysis)

Current distributor price spread (data snapshot)summarize observed prices across online sources.

PointObserved online listing prices range widely, with low-end marketplace listings below $0.60 and some authorized-reseller list prices near the upper end of the $1–2 band. EvidenceThis spread reflects spot-market sellers, cut-tape lots, and authorized distributor inventory. ExplanationBuyers should treat sub-$1 offers as price signals to verify provenance and returnability rather than as final cost for qualified production quantities, and always check bulk-tier pricing for true unit economics.

What drives pricing varianceexplain factors — authorized vs. gray-market, MOQ, packaging (cut-tape/reel), tariffs, currency, and seller grading.

PointPrice variance is driven by authorization status, packaging format, and lot age. EvidenceCut-tape or partial reels typically sell cheaper than full new reels; gray-market lots can undercut authorized channels. ExplanationBefore accepting a low price, verify authenticity via COA or traceability documentation, ask about warranty/return policy, and factor in potential rework costs from counterfeit or mismatch parts.

#3 — Stock & availability trends (Data analysis)

Real-time signals to monitorlist best sources (stock flags, aggregators, marketplace risk evaluation).

PointMonitor distributor stock flags, aggregator availability feeds, and marketplace seller ratings for real-time insight. Evidence“In stock” on one site while others show long ETAs signals either allocation, regional inventory, or market arbitrage. ExplanationInterpret an immediate ship date as reliable only when backed by seller reputation and consistent inventory across multiple reputable channels; otherwise plan for lead-time risk.

Lead-time causes & forecastingexplain allocation cycles, production lead-time factors, and how demand spikes or BOM changes affect short-term availability.

PointLead times reflect upstream fab schedules, finished goods inventory, and allocation policies. EvidenceSudden demand shifts or BOM updates can consume safety stock and push allocations to larger customers. ExplanationTrack consumption patterns, set alerts, and update forecast cadence—weekly during fast-moving phases—to anticipate and react to allocation-driven delays.

#4 — Sourcing & procurement playbook (Method/guide)

Short-term tacticssingle-unit buys, sample sourcing, verified small-quantity channels, and counterfeit checks (visual inspection, lot traceability).

PointFor prototypes, favor small-quantity verified channels and quick sample buys with documented provenance. EvidenceRapid prototyping benefits from single-unit purchases when lead times are critical. ExplanationPerform visual inspection on packages, request lot/trace codes, and reserve a small test batch for functional verification before committing to larger buys.

Long-term procurementmulti-sourcing strategy, authorized distributor agreements, MOQ negotiation, safety stock level guidance and reorder points for US operations.

PointFor volume runs, establish authorized distributor relationships, maintain safety stock, and negotiate MOQs and payment terms. EvidenceA two-supplier strategy plus a safety buffer reduces allocation risk. ExplanationUse a rule of thumbreorder when on-hand equals expected demand for the supplier lead-time plus two weeks of buffer; adjust safety stock based on defect and on‑time delivery KPIs.

#5 — Case studiespurchase scenarios & lessons (Case display)

Small-batch prototype purchasescenario, decision path, and outcome (buy from authorized distributor vs. lower-cost marketplace).

PointA prototype buyer chose a verified small-quantity channel despite a cheaper marketplace option. EvidenceThe slightly higher landed cost prevented hold-ups from failed parts and avoided rework. ExplanationWhen time-to-validate is constrained, the premium for traceability and returns often offsets the apparent savings of the lowest-priced lot.

Bulk procurement & risk mitigationscenario where buyer negotiated price/lead-time; include lessons on qualification, traceability, and supplier audits.

PointA volume buyer secured better pricing by committing to a rolling purchase agreement and supplier audit. EvidenceQualification reduced perceived vendor risk and unlocked lower tiers and consignment options. ExplanationTrack KPIs—on-time delivery, defect rate, and unit cost—to justify future negotiation and to adjust reorder points.

#6 — Action checklistWhat US engineers & buyers should do now (Action suggestions)

Immediate (0–2 weeks)quick checks and purchase tips (verify price authenticity, request COA, order samples from authorized sources).

PointTake fast risk-reduction steps to secure prototypes and short runs. EvidenceQuick wins include ordering one verified sample, requesting COA, and turning on distributor alerts. ExplanationPrioritize actions that reduce technical and supply uncertainty within two weeks and assign ownership to procurement and engineering for rapid follow-through.

Strategic (1–6 months)set up alerts, qualify alternates, lock pricing with contracts, and update BOMs with cross-references (e.g., authorized SI5351A-family alternates).

PointImplement medium-term safeguards to stabilize supply and cost. EvidenceFormal qualification of alternates and alerts reduces scramble buys during spikes. ExplanationOver 1–6 months, engineering should validate alternates while procurement secures agreements and establishes reorder policies tied to demand forecasts.

Summary (Conclusion)

RecapThe SI5351A-B-GTR is a flexible three-output clock generator suited to MCU, FPGA, audio, and comms applications; observed market pricing varies widely and stock signals come from distributor flags and aggregator feeds. Recommended actionsverify provenance, maintain multi-sourcing, set safety stock, and use the short- and long-term checklist to reduce procurement risk and manage pricing volatility.

Key summary

SI5351A-B-GTR is a compact, programmable clock generator offering three outputs and ~200 MHz capability; choose verified samples to avoid counterfeit risk.

Pricing dispersion across marketplaces demands provenance checks—low list prices often carry higher verification and rework cost.

Monitor distributor stock flags and aggregator alerts; implement a two-supplier strategy plus safety stock for US operations.

Immediate actionsorder a verified sample, request COA, enable alerts; strategic actionsqualify alternates, negotiate MOQs and terms.

FAQ

How should I interpret SI5351A-B-GTR pricing?

Treat low online prices as prompts to verify traceability and return terms; compare landed cost after factoring testing, potential failures, and lead time. For production, prioritize authorized channels or qualified suppliers even if unit list price is higher.

What stock signals indicate real availability for the clock generator?

Reliable signals include consistent “in stock” status across multiple reputable sellers, confirmed ship dates, and a short ETA with documented lead-time. One-off “in stock” claims on marketplaces without provenance are higher risk.

What immediate procurement steps cut risk when sourcing this clock generator?

Order a verified sample, request lot traceability or COA, enable distributor alerts, and test the sample in your BOM context. Assign procurement to secure short-term supply while engineering validates functional performance.