The latest datasheet contains dozens of electrical and thermal entries; eight typically determine whether a MOSFET meets system-level targets for efficiency, thermal margin, and EMI. This deep-dive extracts the critical specs, explains how to validate them in the lab, and provides practical metrics and trade-offs for topology selection. Readers will see the term MPMT1002AT5 in part-marking and header fields and learn to interpret datasheet numbers and translate them into design decisions.

This guide is aimed at power-design engineers, component engineers, and test engineers who need reproducible procedures to validate static and dynamic specs. It covers which fields to read first on the datasheet, methods to estimate conduction and switching losses, thermal impedance interpretation, and a checklist to use before prototype build. The word "datasheet" and "specs" are used throughout to align expectations with measured results.

1 — Background: MPMT1002AT5 at a glance

1.1 Key identifiers on the datasheet

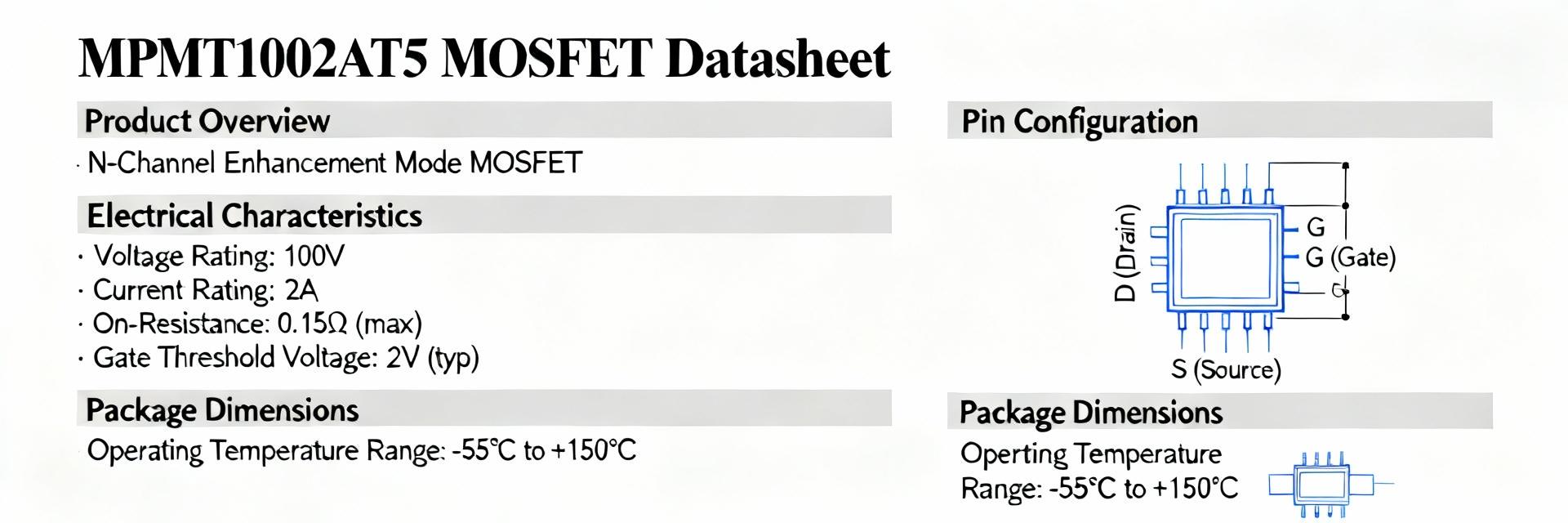

Point: Start by locating the part-number block, package code, marking, revision/date and ordering codes. Evidence: The header typically lists part variants and revision identifiers alongside package outlines. Explanation: Confirm the exact MPMT1002AT5 variant and revision: package code indicates thermal pad and leadframe options, marking correlates to internal binning, and revision/date flags spec updates that affect RDS(on) or thermal tables.

1.2 Target applications and typical topologies

Point: Identify common use cases such as synchronous buck, synchronous boost and point-of-load converters. Evidence: Device power class, VDS rating, and package thermal performance drive suitability. Explanation: Use a rule-of-thumb: select this device for mid-power point-of-load or buck stages where the package thermal pad and RθJA support the application power dissipation at your switching frequency; match switching frequency to device gate-charge and loss profile.

2 — DC specs deep-dive: static electrical characteristics

2.1 On-resistance, threshold, and leakage

Point: RDS(on), VGS(th) and leakage currents define conduction performance and standby budgets. Evidence: Datasheet lists typical and maximum RDS(on) at reference temperature and sometimes at elevated Tj, plus VGS(th) spec and leakage vs. temperature. Explanation: Convert datasheet values to system loss with loss = I^2 * RDS(on) for conduction. Account for temp dependence by using RDS(on) derating from the curve; include worst-case leakage in standby power budgets and for boot-strap or bias supply design.

2.2 Thermal ratings and SOA considerations

Point: Extract RθJA, RθJC, Tj(max) and any thermal impedance curves. Evidence: Thermal tables and graphs show how junction temperature rises with power and how RθJA varies with PCB copper area. Explanation: Map thermal impedance curves to your PCB by matching copper area and layer count to the plotted RθJA points. Read Safe Operating Area if present and derate current or duty cycle where the SOA or Tj limit would otherwise be exceeded; prepare a short checklist of thermal fields to capture.

Thermal ParameterWhy it matters

RθJA / RθJCMaps device power to junction rise and informs copper area needed

Tj(max)Defines allowable dissipation for reliability and margin

Thermal impedance curvesEnable transient power handling and pulse-width planning

3 — Dynamic specs & switching metrics

3.1 Gate charge, capacitances, and switching times

Point: Qg, Qgs, Qgd and capacitances (Coss, Crss) determine driver sizing, switching loss, and dV/dt behavior. Evidence: Datasheet curves provide gate-charge vs. VGS and capacitance vs. VDS. Explanation: Use these specs to estimate gate-driver power (Pdriver = Qg * Vdrive * fSW) and to size the driver for targeted rise/fall times. Map datasheet test conditions (VDS, ID, VGS) to your circuit operating points to ensure comparable interpretation.

3.2 Loss estimation and example methodology

Point: Combine conduction and switching contributions to estimate total device loss. Evidence: Required inputs include RDS(on) at operating Tj, Qg, switching frequency and observed dV/dt. Explanation: Step method — 1) calculate conduction loss using I^2·RDS(on) averaged over waveform; 2) estimate switching loss from energy per transition (use published curves or approximate with E = 0.5·Coss·VDS^2 for capacitive contribution plus gate-charge-related switching); 3) add driver losses and margin (suggest 20–40% margin or specify thermal headroom in °C). Document assumptions for repeatability.

4 — How to validate MPMT1002AT5 datasheet numbers in the lab

4.1 Recommended test setups & conditions

Point: Reproduce datasheet tests with minimal but correct equipment: pulsed-current source, calibrated scope, Kelvin fixturing and a thermal chamber if needed. Evidence: Datasheets often specify pulse widths, duty cycle and temperature for RDS(on) and gate-charge tests. Explanation: Match pulse width and duty cycle to avoid self-heating, use Kelvin connections for low-resistance measurements, and ensure probe grounding and bandwidth are adequate. Include a short checklist for parity: ambient, pulse width, and probe method.

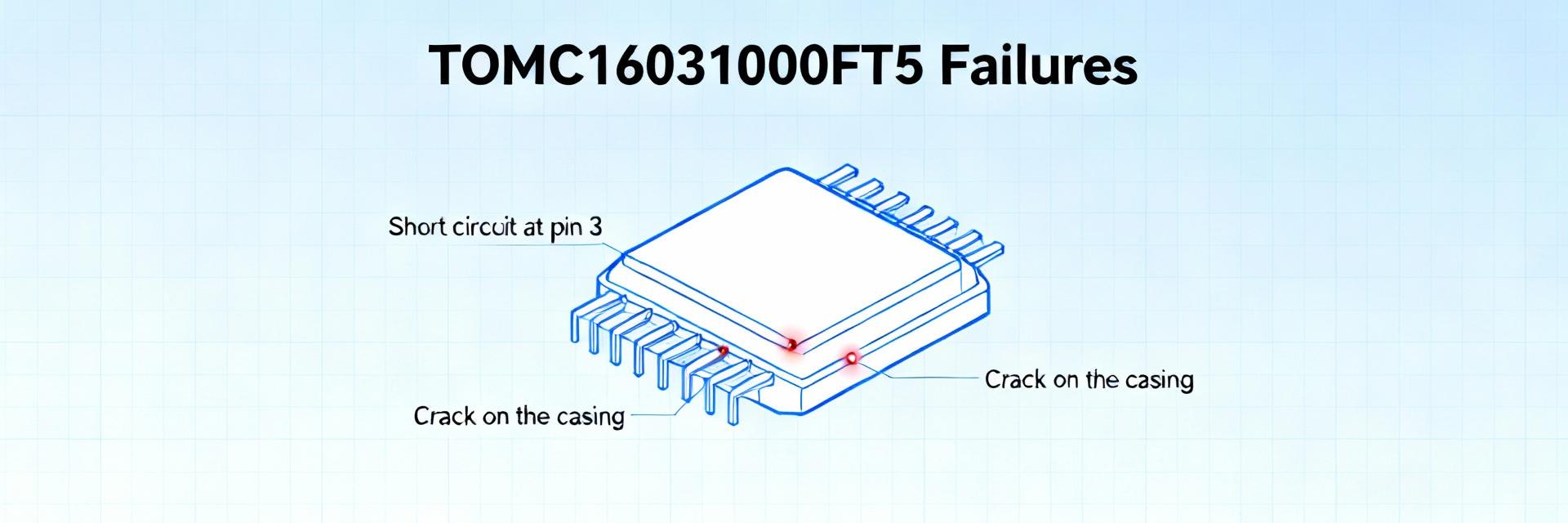

4.2 Interpreting discrepancies and requesting vendor data

Point: Mismatches arise from test-condition differences, lot variance or measurement errors. Evidence: Typical vendor responses include raw waveform data and measurement conditions. Explanation: When results differ, record test parameters, provide waveforms, and request vendor raw data and lot traceability. Document discrepancies with clear tables of expected vs. measured values and suggest targeted re-tests under matched conditions before concluding part performance issues.

5 — Application case: Using the MPMT1002AT5 in a synchronous buck (layout & thermal notes)

5.1 Thermal profile, PCB layout, and packaging trade-offs

Point: Translate thermal specs into layout actions: copper area, via count, and thermal pad guidelines. Evidence: Datasheet thermal recommendations and package land patterns indicate required pad size and via placement. Explanation: Provide layout guidance: maximize top-layer copper from the thermal pad, use an array of thermal vias to inner planes, and follow vendor pad dimensions. Package selection affects thermal path; choose variants with exposed pad for higher dissipation.

5.2 EMI, snubbing, and robustness practices

Point: Use Coss and dV/dt data to plan snubbers, layout, and decoupling. Evidence: Switching-capacitance curves and recommended circuit examples indicate snubber placements. Explanation: Reduce EMI by minimizing loop area of switching node, placing snubber or R-C across switch when dV/dt transients are high, and adding adequate bulk and high-frequency decoupling close to the device. Validate with near-field probing on the layout.

6 — Quick decision checklist & next steps for designers

6.1 Pass/fail checklist driven by datasheet specs

Point: Use a compact checklist keyed to datasheet fields. Evidence: Each acceptance rule references a specific datasheet table or graph. Explanation: Items include power-rating match, RDS(on) margin at operating Tj, thermal-pad plan vs. RθJA, gate-driver compatibility with Qg, switching loss estimate at fSW, leakage at operating temperature, and SOA/derating. Use this as a go/no-go before prototype BOM freeze.

6.2 When to seek alternatives or supplementary data

Point: Trigger alternatives when thermal headroom is marginal, leakage is high, or switching behavior degrades system EMI. Evidence: Supplemental reports that are useful include lot-average thermal impedance and extended gate-charge curves. Explanation: Request vendor lot statistics, extended waveforms, and application-characterization tests if any checklist item is marginal; consider alternate parts when derating would force a change in topology or significant layout rework.

Summary

Converting datasheet entries into actionable design metrics requires focusing on DC and dynamic specs, mapping thermal impedance to your PCB, and reproducing key measurements in the lab. Use the conduction and switching loss methodology, follow layout and snubbing recommendations, and run the decision checklist before prototype build. The MPMT1002AT5 datasheet can be the source of reliable design inputs when test parity and conservative margining are applied.

Key Summary

Extract RDS(on), its temperature dependence, and VGS thresholds from the datasheet to compute conduction losses and gate-drive needs, then margin those values for worst-case Tj.

Use RθJA/RθJC and thermal impedance curves to size copper area and vias; compare calculated junction rise to Tj(max) and apply derating if headroom is limited.

Estimate switching loss using Qg, Coss and switching frequency; include gate-driver power (Qg·Vdrive·f) and add a thermal margin of 20–40% for reliability.

Validate with pulsed RDS(on), gate-charge, and thermal-rise tests using Kelvin connections and matched pulse conditions to datasheet test specs.

FAQ

How should an engineer use the MPMT1002AT5 datasheet to calculate switching losses?

Answer: Start with device Qg and Coss curves at the operating VDS and ID, then compute energy per transition using published waveforms or approximations (E ≈ 0.5·Coss·VDS^2 for capacitive charge). Multiply by switching frequency and add conduction losses (I^2·RDS(on) averaged over the waveform) and gate-driver power. Document assumed dV/dt and test conditions for repeatability.

What test conditions are critical to reproduce datasheet RDS(on) for MPMT1002AT5?

Answer: Match pulse width, duty cycle and junction temperature to the datasheet references. Use short pulses to prevent self-heating, Kelvin sense connections for the low-side measurement, and specify ambient or controlled Tj where the datasheet gives values. Note probe grounding and bandwidth as sources of error.

Which thermal parameters from the datasheet determine PCB copper requirements?

Answer: RθJA and thermal impedance curves are primary; also use RθJC and recommended land pattern guidance. Map the datasheet RθJA points to your expected copper area and via count: larger copper and thermal via arrays reduce RθJA and lower junction temperature for a given power dissipation.